In the 1990s, if you had seen anyone pull out a camera at a family gathering or weddings, chances are you had a roll of Kodak film inside it. This brand used to be a part of people’s lives.

But here comes the plot twist: Kodak is the company that taught the world how to capture memories, but couldn’t save its own. By 2012, the giant that once held 90% of the U.S. film market filed for bankruptcy.

Meanwhile, Fujifilm, another name from the film era, was facing the same situation. There was no film left in the future because digital cameras were destroying it. Yet, while Kodak crumbled, Fujifilm thought of reinventing itself. Fujifilm transformed into a multi-billion-dollar innovator from cosmetics to healthcare to advanced cameras.

So why did one giant collapse while the other rose stronger than ever? Let’s explore the fascinating story of Fujifilm’s survival and Kodak’s downfall, and what every business today can learn from it.

The Golden Age of Film: Kodak’s Era of Dominance

The Consequences of the Digital Revolution: A “Crappy” and Vanishing Business

How Fujifilm Overcame Crisis and Successfully Reinvented?

The Golden Age of Film: Kodak’s Era of Dominance

Long before the digital wave, both Kodak and Fujifilm thrived in a business model that looked bulletproof. While they made cameras, the real money came from film and photo development. Kodak perfected what it called the “silver halide” strategy: give away or sell cameras cheaply, then make big profits when people came back for film, chemicals, and paper. It was the same playbook used by Gillette with razors and blades, or printer makers with printers and ink.

Fujifilm wasn’t far behind. In 1986, it brought disposable cameras to the masses, and Kodak followed in 1988. By 2000, film was still king, making up 72% of Kodak’s revenue and 66% of its operating income, while Fujifilm relied on it for 60% and 66% respectively. What made film such a fortress business was its complexity. A single roll wasn’t just plastic and chemicals; it was a masterpiece of engineering. Color film had 20+ ultra-thin layers, each one sensitive to different colors of light, built with microscopic precision.

As Kodak’s former VP Willy Shih put it, making color film was like “running 24 layers of advanced chemicals at 300 feet per minute, all in total darkness.” That complexity created high entry barriers. Dozens of companies once produced black-and-white film, but when color came in, only a handful survived. In the end, the market became a two-horse race between Kodak and Fujifilm, with Agfa and Konica trailing behind. Despite fierce price wars, Fuji famously undercut Kodak in the 80s and 90s; the business remained secure, profitable, and predictable for decades.

The Consequences of the Digital Revolution: A “Crappy” and Vanishing Business

2001: The Peak Before the Fall

- Film sales reached their peak worldwide.

- But as the president of Fujifilm warned: “A peak always conceals a treacherous valley.”

- Sales started shrinking slowly, then rapidly, eventually dropping 20–30% per year.

- By 2010, global demand for photographic film had fallen to less than one-tenth of what it was in 2000.

Shift from Film to Digital

- The market didn’t disappear overnight; it changed.

- With the rise of the internet and personal computers in the 90s, consumers moved to digital cameras.

Problem: Digital imaging relied on semiconductors, a platform completely different from film manufacturing.

The Downside of Going Digital

- Unlike film, digital camera technology was modular; any engineer could assemble a camera from parts.

- Entry barriers vanished; dozens of companies entered the market.

- Kodak’s CEO, Antonio Perez, called digital cameras a “crappy business” because: margins were extremely low and products became commodities instead of premium goods.

GoPro Example – The Commoditization Effect

- A California surfer (GoPro founder) disrupted the video recorder market.

- But soon, even GoPro was outcompeted by cheaper Chinese manufacturers.

- This highlighted how low entry barriers crushed profitability.

Kodak’s Financial Struggles

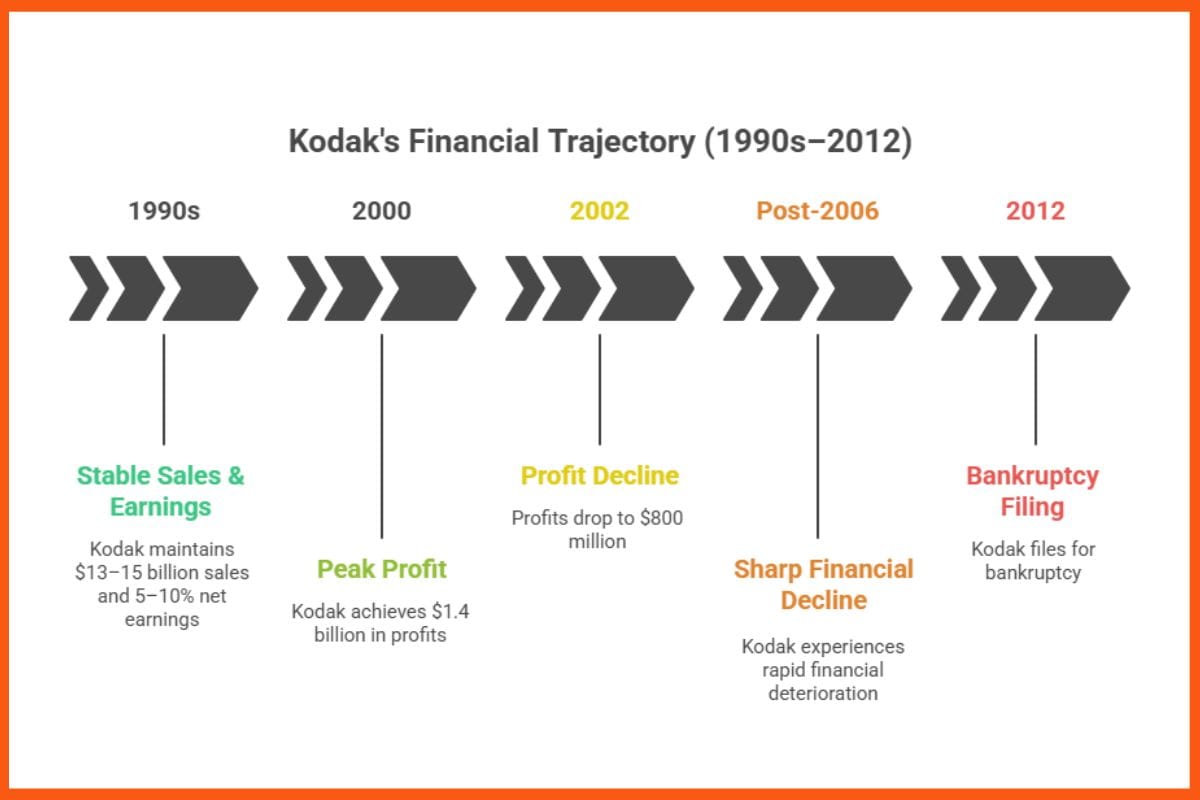

- 1990s: Kodak sales hovered between $13–15 billion with solid 5–10% net earnings.

- 2000: Profits of $1.4 billion.

- 2002: Profits fell to $800 million.

- Post-2006: Sharp financial decline leading to bankruptcy in 2012.

Kodak’s Digital Camera Paradox

Kodak sold a lot of digital cameras:

- 2005: Captured 21.3% of the U.S. market (ranked #1).

- Sales grew 15% that year.

- But globally, it lost market share.

- 1999: 27% share → 2003: 15% → 2010: 7%.

The main problem: They weren’t profitable.

- A Harvard study revealed Kodak lost $60 per digital camera in 2001.

- In 2011, Kodak’s film sales made $34M profit, but digital cameras lost $349M.

Fujifilm Faced the Same Storm, but Survived

- The president admitted: “The photographic film market had shrunk much faster than we expected.”

- Between 2005 and 2010:

- Color film sales fell from ¥156 billion → ¥33 billion.

- Photo finishing dropped from ¥89 billion → ¥33 billion.

- Unlike Kodak, Fujifilm not only survived but sustained itself by reinventing itself.

How Fujifilm Overcame Crisis and Successfully Reinvented?

When the film market collapsed (falling to less than 10% of its 2000 size by 2010), Fujifilm was in deep trouble. Film once made up 60% of its sales, but sticking to it would have meant certain death, just like Kodak. Instead, Fujifilm managed to grow revenue by 57% over the next decade, while Kodak’s sales fell by 48%.

Bold Leadership and Vision 75

- In 2000, Shigetaka Komori became president of Fujifilm.

- By 2004, he launched a six-year plan called VISION 75 (named after Fujifilm’s 75th anniversary).

- The mission was clear: “Save Fujifilm from disaster and ensure its viability as a leading company with sales of 2–3 trillion yen a year.”

Restructuring and Innovation Push

- Downsized the film business by closing redundant facilities.

- Merged research divisions into one centralized R&D hub to drive innovation and collaboration.

- Accepted that digital cameras couldn’t replace film profits and looked for new growth engines.

Technology Audit and Market Mapping

- Komori ordered R&D to inventory Fujifilm’s technologies and compare them with global market needs.

- After 18 months, engineers identified areas where existing expertise could fuel new businesses:

- Pharmaceuticals

- Cosmetics

- Highly functional materials

Winning Bets on Emerging Markets

- LCD Screens: Adapted a photo film technology to create FUJITAC, a high-performance film essential for LCD panels. Today, FUJITAC controls 70% of the global market for protective LCD polarizer films.

- Cosmetics: Built on its expertise in gelatin and collagen (key for both photo film and human skin). In 2007, Astalift, a skincare and cosmetics brand, became successful in Asia.

Growth Through Acquisitions

- Used M&A to speed up entry into new industries. Key moves included:

- Toyama Chemical (2008): Entry into pharmaceuticals.

- Fujifilm RI Pharma: Strengthening radiopharmaceuticals.

- Fuji Xerox (2001): Became a consolidated subsidiary after increasing stake by 25%.

Transformation by 2010

- 60% of revenue and two-thirds of profit came from film in 2000.

- Imaging made up less than 16% of revenue by 2010.

- Fujifilm had become a diversified technology powerhouse spanning healthcare, cosmetics, imaging, and advanced materials.

Conclusion

Fujifilm and Kodak’s story teaches us a valuable lesson about coping with change. Kodak failed because it did not change from what it had always done. On the other hand, Fujifilm accepted the change. The company started new types of businesses using its knowledge.

In today’s world, Fujifilm is a leading company in healthcare, skincare, electronics, and many other fields. With Kodak, which used to be a big name in cameras, others should be cautious about not innovating. Fujifilm succeeded because it was willing to try new things and not just rely on its old business. It is important to be able to change and plan for the future based on the story.

FAQs

Why did Kodak fail while Fujifilm survived?

Kodak failed because it resisted change and stayed dependent on film, while Fujifilm embraced diversification into cosmetics, healthcare, and electronics, ensuring survival beyond photography.

What was Fujifilm’s Vision 75 strategy?

Launched in 2004 by Fujifilm president Shigetaka Komori, Vision 75 was a six-year transformation plan that restructured operations, drove innovation, and diversified the company into new industries like healthcare and electronics.

Did Kodak invent digital cameras?

Yes, Kodak developed the first digital camera prototype in 1975 but failed to commercialize it effectively, fearing it would cannibalize its profitable film business.